Matthew Carpenter-Arévalo

Contributor

Matthew Carpenter-Arévalo is a former Google and Twitter manager and current CEO of Céntrico Digital, a Latin American-based digital agency.

More posts by this contributor

In 2012, the emblematic podcast This American Life did a special on politics in Afghanistan. They noted that in order to be a politician in Afghanistan, one needs to command a personal armed militia. That’s how politics is practiced in a fragmented country with a long history of violence, and without a stable, credible centralized authority.

In the quaint and relatively peaceful Andean nation of Ecuador, snuggled between Colombia and Peru, a similar phenomenon takes place: politicians don’t require armed guards, but they do require their digital equivalent: Twitter troll centers, or businesses that sell online harassment as a service.

Indeed, much of the country’s public debate, or lack thereof, is now defined by the anonymous accounts that threaten, cajole and, ultimately, aim to silence voices of dissent. Though Ecuador may be too small to register on the Twitter executive team’s radar, under their noses the lucrative business of weaponizing the platform is already being exported to other countries in the region. The abuse of Twitter through troll centers not only threatens the company’s vision to become the world’s agora, it may also be putting lives at risk.

Imagine a populist president raging against his country’s elites, including the news media, as corrupt enemies of the people. Because of his innate distrust of journalists, he uses Twitter to speak divisive rhetoric directly to his digital faithful. At his disposal is an army of hardcore supporters ready to do his bidding, echo his message and attack anyone who dares disagree. If you recognize the character in this story, it’s probably because you’re familiar with Rafael Correa (56), the populist former president of Ecuador (January 2007- May 2017).

Correa now lives in Belgium and cannot return to Ecuador without facing trial for having ordered the kidnapping of a political opponent. The opponent in question fled Ecuador to neighboring Colombia in 2012, where he was trailed by members of Ecuador’s secret police and briefly kidnapped. Witnesses from the state security apparatus have since come forward to point the finger at Correa as the intellectual author of the crime.

The staunchest defenders of concentrated power are those who hold that power.

Correa denies the charges and claims they are merely politically motivated theater orchestrated by his former mentee and now sworn enemy, current Ecuadorian president, Lenín Moreno. But even if that were the case, Correa still has a number of other uncomfortable questions to answer to the Ecuadorian people. Since 2013, Latin America has been rocked by a corruption scandal called Lava Jato (the car wash) in which the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht paid bribes to politicians across the region to win public works projects (the Netflix series O Mecanismo, or The Mechanism in English, dramatizes the unfolding of the case in Brazil). In total, Odebrecht is said to have paid $788 million U.S. dollars in bribes in 12 countries in exchange for government contracts.

As a result of Lava Jato, former presidents in Brazil and Panama are in jail. In Peru, two former presidents are incarcerated, one is being held prior to an extradition hearing in California and, in April of this year, one dramatically committed suicide when police came to escort him to prison.

Ecuador’s government was no exception to the Brazil construction firm’s corruption: Rafael Correa’s former vice president and preferred successor, Jorge Glas, was convicted in December of 2017 of having directed multi-million-dollar contracts to the Brazilian firm in exchange for massive payoffs hidden through a series of offshore accounts. Indeed, Glas’s poor approval rating was the cause for Correa asking Moreno to come out of retirement and run for president.

Were Lava Jato not enough to spark wide-scale public outrage, a new scandal called Arroz Verde (green rice), revealed in May of 2019, exposed how the Correa election campaigns had government contractors cover expenses in order to flaunt spending restrictions. Numerous former ministers from the Correa government are currently either in jail or awaiting trial, under house arrest or have fled the country. Correa’s legacy as a tough yet modernizing progressive president is currently threatened by corruption scandals of previously unimaginable proportions.

It wasn’t supposed to be that way. When Rafael Correa was elected in 2007, Ecuador was emerging from a period of political, social and economic instability. In 2000, the country’s banks failed and the following economic collapse lead to Ecuador adopting the U.S. dollar as its official currency. Two years prior, a war with neighboring Peru resulted in the loss of a significant portion of Ecuador’s claim to the Amazon rain forest. In the early 2000s, close to 10% of the population, more than a million Ecuadorians, migrated to Spain and the United States in search of work. Three democratically elected presidents in a row were overthrown by street protests, including one colorful actor who was disposed after only six months in office. He was officially declared to have abandoned his role due to mental incapacity.

A relatively obscure leftist economics professor, Correa had a short stint as the country’s finance minister in 2005 during a transitional government. He left his post after a public spat with the International Monetary Fund. The IMF demanded Ecuador use its oil revenues to pay off its staggering external debt. Correa insisted that the country’s first priority should be its social debt and that the monies should be invested in health and education.

The fight vaulted Correa into the public eye and he was able to ride the momentum all the way to the presidency, defeating the country’s richest man in a run-off vote. Through his bombastic rhetoric, Correa took aim at the country’s business, political and media elites and fingered them as the origin of the country’s problems. He captured the populations’ unrest through the campaign slogan Dale Correa, which means both “Go Correa” and “Give ‘Em the Belt!”

Once in office, Rafael Correa set about an aggressive reform agenda. He rewrote the Constitution, the country’s 20th, and re-organized the state apparatus. Fueled by record high oil prices, Correa invested massively in highways, schools, hospitals and much-needed infrastructure like hydroelectric dams.

Shunning the country’s traditional alliance with the United States, Correa turned instead to China, a decision that, as The New York Times has documented, ended in billions of dollars being misspent on Chinese-built hydroelectric dams that don’t actually work at full capacity. In addition, China sold Ecuador technology which, though promoted as a 911 public safety tool, was used by the Correa government to keep tabs on and harass political opponents.

When Americans talk about Donald Trump’s latest scandals, Latin Americans mostly roll their eyes. After all, Latin Americans have seen the Donald Trump character interpreted by numerous strongmen, or caudillos, throughout the region’s history. They have even seen how it plays out on Twitter. Both Venezuela’s late President Hugo Chávez and Rafael Correa saw in Twitter an opportunity to go around their countries’ respective traditional media and speak directly to the citizens, a benefit of social media President Trump has also touted.

Correa would regularly engage in banter with citizens and do the work of government through tweets. His famous expression Favor Atender (please see to this) followed by a mention of a high-level minister or official was his calling card to government to get directly involved in resolving citizen complaints brought to his attention through Twitter. Correa went so far as to host lunches in the presidential palace for the Twitter users who most supported and defended him. The novelty of the hands-on approach soon revealed its dark side.

What happened next is the stuff of Benghazi-like conspiracy theories.

Many historians point to the 30th of September 2010 as the date when Rafael Correa started breaking bad. The day began as any other in the perpetually sunny capital of Quito. As mountain climbers will note, people at high altitudes sometimes make bad decisions due to the thin air, and Ecuador’s capital Quito stands at 9,350 feet. On this day, the National Police declared to the news media they were going on strike to protest a restructuring of their compensation packages. A group of police officers took a regiment and Rafael Correa decided that the best course of action was to go in person and confront them. Surrounded by his handlers and sustaining himself with a cane after a recent knee operation, Correa berated the police officers, ripped his shirt open like a tropical hulk and dared the officers to shoot him in the chest. “Here I am and if you want to kill me, go ahead and kill me!” he cried.

What happened next is the stuff of Benghazi-like conspiracy theories. Depending on who you believe, Correa was either kidnapped and taken to a police hospital or went there voluntarily. The army eventually responded and a shoot-out ensued between the police and the army in the streets of Quito. Five people were killed, including three police officers, a soldier and a citizen. The president was eventually rescued by the military and restored to his functions about 12 hours after the debacle began. In a country used to coups and presidential turnover, democracy seemed to have won.

From the beginning of his time in office, Rafael Correa was determined not to suffer the fate of his overthrown predecessors. Having experienced the potential for that fate up-close, Rafael Correa reacted by removing his tyrannical constraints. Correa became increasingly belligerent on and off Twitter. Notoriously thin-skinned, Correa made a habit of throwing people in jail for flipping him off. He even stopped his motorcade to personally stick his finger in the nose of an irreverent teenager who Correa later had thrown in jail (the young man was eventually freed after apologizing).

Correa continued his crusade against journalists who wrote things about him with which he didn’t agree. Sometimes he insulted and threatened them; other times he hit them with multi-million-dollar lawsuits, which friendly judges were more than willing to oblige with speedy trials and favorable outcomes for the president.

The Ecuadorian government, it was leaked, spent millions on the Italian firm Hacking Team to spy on its citizens. On his weekly traveling Saturday Show, broadcast across radio, television and the internet, Correa would read tweets from people who insulted him and then reveal their true identities and addresses and call for retaliation. Whilst on the world stage, Correa portrayed himself as a defender of free speech by famously receiving Julian Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy in London; on the homefront, Correa hunted down dissenters and used the entire state apparatus to punish whistleblowers.

The Correa government’s harassment wasn’t only digital: as Gimlet’s Reply All podcast documented in their story Favor Atender, one of Correa’s most fervent Twitter adversaries, Gabriel González, received death threats in February 2015 after making memes that poked fun at things like the government’s sometimes absurdly inefficient healthcare system. Worried for his safety, Gabriel left Quito. Then, at his hideout hundreds of miles away, he received a Sopranos-like wreath of flowers along with pictures of his wife and child (Disclosure: Gabriel briefly freelanced for me as a contractor before the aforementioned events took place), stating it would be a shame if anything were to happen to them. When the price of oil started to decline and Correa’s spending power was curtailed, his popularity began to waver. After this, the president’s digital antics only worsened.

Whenever anyone tweeted something unpleasant to the president, they immediately faced a barrage of incoming attacks and insults.

Carlos Andrés Vera is one journalist for whom online harassment become offline harassment. A documentary filmmaker, publicist and former editor of the Ecuadorian edition of Soho Magazine, Carlos Andrés drew the ire of the Correa government by being highly critical of the administration, including its management of the Ecuadorian Amazon and its mishandling of the safety of the uncontacted tribes that are currently threatened by oil exploitation in and around the Yasuní National Park.

A prolific tweeter, Carlos Andrés frequently engaged his trolls, as well as numerous government ministers and operators. He first felt threatened when a troll account published a photo of his son that was on his phone but that he hadn’t published anywhere. The troll account suggested making a pornographic movie with Carlos Andres’s underaged son.

On more than one occasion he was threatened on the street by individuals who made reference to his digital activism. Then, in 2015, Carlos Andrés was the victim of a secuestro express, or express kidnapping. Usually victims of secuestro express are roughed up and then driven from bank machine to bank machine to empty their account, and then set free. In his case, Carlos Andrés was held and beaten for a number of hours, but the perpetrators never drove him to a bank machine nor did they even take his wallet. The event occurred at a time when Carlos Andrés was involved in fierce and aggressive Twitter debates with high-level government authorities. Carlos Andrés is convinced the incident was coordinated by the government and meant to intimidate him into digital silence. According to Carlos Andrés, “no government, not even Russia or Venezuela, was as advanced as the Correa government in weaponizing Twitter against its citizens.”

Out for a run on a recent Saturday, I noticed a particularly dirty street close to an official billboard declaring that “Quito is once again great.” In May of this year a new mayor had taken office after a surprise victory, slipping his way through a crowded group of 18 candidates and crowning himself mayor despite winning less than 30% of the popular vote (in Ecuador voting is mandatory, and though run-off elections are held at the presidential level, they are not used for municipal elections).

The new mayor, Jorge Yunda, was a former Correa collaborator who had since distanced himself from the now out of favor ex-president. The owner of a number of radio stations whose frequencies were granted in a process many consider to be less than transparent and fair, Yunda shamelessly copied Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan and adopted it to Quito. Unlike Trump, Yunda resisted the temptation to name and shame a public enemy.

Despite the candidate’s poor showing in the popular vote, Yunda’s team brazenly plastered Quito with “Quito is now great again” billboards, despite having yet to accomplish anything. Angry with the juxtaposition of a government declaring victory whilst having a major garbage management crisis on its hands, I took a picture and trolled the mayor.

.@lorohomero, explain to me once again, this time slowly, how is it that Quito is great again?

By the time I finished my run I had regretted my tweet. The tweet wasn’t going to accomplish anything and Twitter doesn’t need more angry voices shouting into deep internet space. I thought about deleting it, and when I arrived home and I opened my phone it took me by surprise to see that in 10 minutes the tweet had received 134 responses, including one from the mayor asking me for more time to get his house in order.

The volume of responses was surprising because it was early on a Saturday morning, so I dug a little further and quickly picked up on a familiar pattern: many of the accounts of the respondents had less than 50 followers and they only followed a handful of people. Their usernames were often combinations of names plus a string of numbers. Most were saying more or less the same thing in response to my tweet. Soon thereafter, Twitter began automatically deleting some of the responses as if in recognition that the pattern of behavior was malicious.

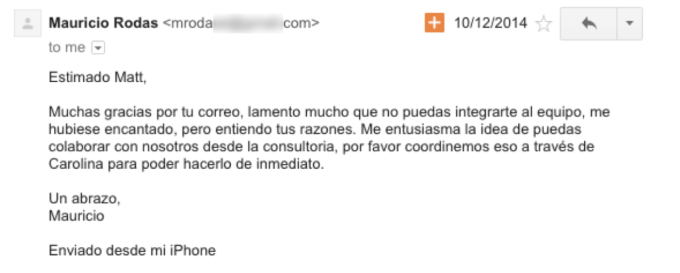

I say the behavior was familiar because I had seen it before. I was a vocal critic of the outgoing municipal administration (May 2014-May 2019) lead by Mauricio Rodas (44). The mayor then reached out through a mutual friend and offered me a job, which I turned down.

Dear Matt, Thank you for your email. I’m sorry you won’t be able to join the team. I would have liked you to but I understand your reasons. I’m really enthusiastic about the idea that you might be able to collaborate with us through a consulting gig. Let’s please set this up through Carolina so we can do this immediately. A hug, Mauricio.

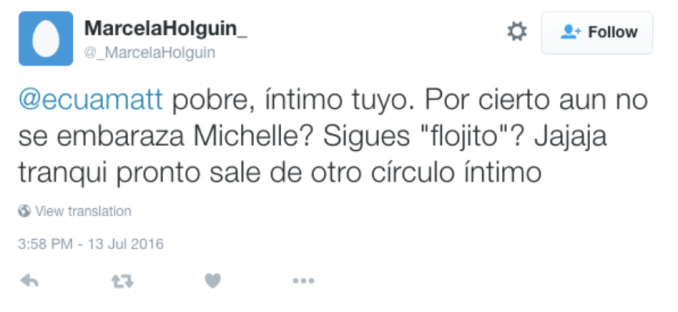

Though my relationship with the mayor was cordial, I continued to offer my critique of his administration’s work. After some time I began to receive messages that attacked me and used personal information, including a number of tweets that attacked my and my wife’s fertility.

@ecuamatt poor guy, by the way is your wife (Michelle) pregnant yet? Can you not yet get it up? Hahaha

Aside from its crudeness, what was surprising was that the then-mayor (2014-2019), Mauricio Rodas, had been elected to counter the increasingly overbearing influence of Rafael Correa. Promising to stand up to the president, Rodas declared that it was time for a new form of politics without the tricks and dirty games popularized by the Correa government. Yet here was Mauricio Rodas using the same means by which Correa attacked and silenced his critics.

A company close to Rafael Correa was the first in Ecuador to begin to monetize the practice of Twitter trolling.

I researched my trolls and noticed a number of patterns between their accounts and a number of accounts of certain high-level municipal officials who appeared to be outsourcing the management of their twitter profiles, including who they followed and which images they used in their profiles and their posts. I then prepared a dossier that pointed to the intellectual authors behind the fake accounts and, in good faith, asked the mayor and two of his advisors to look into the kind of behavior that was being undertaken on his administration’s behalf. I asked them to consider the impact on democratic culture and public debate should politicians like him replicate the behavior of silencing critics through intimidation tactics. I received no reply, though the tweets and most of the accounts that attacked me were deleted. The trolling of the mayor’s critics, however, continued. One of the recipients of my dossier, Rodas’ communication secretary, later became a communications advisor to the incoming Yunda administration.

A company close to Rafael Correa was the first in Ecuador to begin to monetize the practice of Twitter trolling, and Twitter itself was uncomfortably close to this company. Ximah Digital was started by young businessmen from the port city of Guayaquil whose main asset was their close connections to the government. When Twitter began selling ads in Latin America in 2012, it hired the region-wide firm Internet Media Services (IMS) to re-sell its advertising products in the region. Twitter then hired me in 2013 to manage its relationship with IMS (because I worked from a country in which Twitter had no office and am not an American citizen, I was technically hired as a foreign contractor). IMS, an accomplished digital re-seller with operations in much of Latin America, did not have an office of its own Ecuador and thus used Ximah Digital as its official national re-seller.

IMS choosing Ximah as its re-seller was a strange decision, as the small digital agency did not have established relationships amongst the country’s largest brands. Ximah did, however, have high-level government connections, and the government quickly became Twitter’s largest client in Ecuador.

During my time managing the relationship between Twitter and IMS, numerous individuals came to me with accusations that Ximah was managing troll centers whilst acting as the country’s exclusive Twitter sales channel, but I initially didn’t take the threats seriously. The accusations mostly came from individuals aligned with the opposition and, in that moment, I naively thought they were politically motivated. I went so far as to unwittingly take Ximah representatives to meetings with political actors Ximah was allegedly trolling and I defended Ximah publicly. I also don’t recall raising the issue with IMS before I left Twitter in May of 2014.

Ximah then lost plausible deniability on the 5th of September 2014 when a video circulated on social media showing that a number of well-known troll accounts were controlled by Ximah Digital employees. IMS responded to the controversy by firing Ximah Digital and opening its own office. Afterwards, Ximah went quiet for some time, then re-launched itself as a digital consultancy focused on political marketing.

When it worked defending Rafael Correa, the troll centers were easy to detect. Usually the troll accounts tweeted the exact same message as every other troll account in an attempt to control trending topics. The government also used its large number of verified accounts, which hold an extra weight in Twitter’s trending topic algorithm, to control the day’s conversation. The troll accounts could be brutal: Whenever anyone tweeted something unpleasant to the president, they immediately faced a barrage of incoming attacks and insults.

So how does one pay for trolling services? According to past reporting and confirmed by past and current employees, the government would often disguise contracts as general social media management RFPs (request-for-projects), then ensure their provider won the contract. In other instances companies were overpaid to provide legitimate services and there would be an agreement beforehand to provide trolling services in addition to the legitimate services.

Tracking the contracts can be tricky: As the investigative journalists at the leak-publishing site Milhojas have reported, a network of over 16 agencies, some of whom listed unaware farm-workers as their general managers on official documents, earned hundreds of thousands of dollars in government contracts. Many of these agencies shared a single official address, the same address as Ximah Digital.

According to company insiders, Ximah has since sophisticated its operation and now exports its services to other countries in Latin America. Whereas reverse image searches used to reveal the origin of their fake profile pictures, Ximah now scours the Ecuadorian coastal provinces and takes pictures of digital exiles to use their unique pictures as profile images. Ximah has also invested in technology, including AI, to enable automatic responses that are no longer copy-paste and therefore harder to detect. Ximah also trains other digital agencies to be trolls: Former employees from Ximah and employees from other local agencies, including agencies that manage major international clients in industries such as telecommunications, confirmed that Ximah trained their staff how to troll.

If companies like Ximah were founded because of an ideological conviction and affinity with Rafael Correa, they no longer have any qualms about who they work for. One morning I received a WhatsApp message alerting me to a corruption scandal involving a politician that used to be aligned with Rafael Correa and who was running for mayor of Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city. The sender’s number came from Cambodia, which was strange. The language and the aesthetics of the “leaks” page was reminiscent of past work I knew to be from Ximah: an anonymous source then confirmed that Ximah had been hired to manage the slanderous campaign on behalf of Cynthia Viteri, the eventual winning candidate of Guayaquil’s municipal elections. That fact was also confirmed by a political operative close to the Viteri campaign. Viteri’s political party was meant to be the sworn enemy of Rafael Correa. Viteri herself was the victim of Ximah trolling. In numerous campaigns throughout the years, Viteri promised a break from the Correa-era demagoguery… and yet.

Rafael Correa eventually made a career defining miscalculation. Though prior to leaving office Correa reformed the constitution he authored in order to remove the term limits he once insisted upon, he left power temporarily in the hands of his first vice president, the one not in jail for corruption charges, Lenín Moreno.

Tensions between the out-going and in-coming presidents started to show in the campaign, but no-one anticipated the complete 180 that would happen when the wheelchair bound Moreno would assume office. Throwing his predecessor and former mentor under the bus, Moreno promised to investigate and prosecute corruption “caiga quién caiga,” or regardless of who falls. Correa went berserk. Moreno, true to his promise, lost his first and second vice presidents to corruption charges. Moreno also held a referendum to reinstate term limits.

Correa spends his days tweeting hate from an attic in Belgium to his weakened but still dangerous troll army. He, the man who once wielded the power of a state against his enemies, now wallows in his own victimhood. So belligerent were his posts that Facebook closed his account. Twitter hasn’t censored him. Correa talks about returning to Ecuador as a vice-presidential candidate in two years. Ecuador’s weak institutions and strong journalists tremble at the thought.

In his drawn-out interview with Joe Rogan, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey speaks sincerely about the desire to have Twitter become the world’s discussion form. When Twitter works well it can foster debate and generate otherwise impossible interactions between people from all walks of life. It is clear that Jack firmly believes in this mission.

At the same time, Jack is notoriously tone-deaf, as was put on display when he tweeted about the benefits of vacationing in Myanmar without so much as a thought for the victims of the Mynmar government’s ongoing genocidal campaign against its Muslim population. As a former insider and as a close watcher of Twitter’s growth and evolution, I am not convinced Twitter really feels the urgency to make its platform a safer space for healthy debate and accurate information.

Twitter’s indifference is Latin America’s loss. For much of the history of Latin America, media ownership has been concentrated in the hands of a few who generally held sway over public opinion. Media outlets often belonged to prominent businessmen from important industries. The concentration of power in the hands of a few brokers from business, media and politics represented a Petri dish for corruption.

Twitter is raw, open and immediate, allowing the crowd to determine relevance.

Twitter blew up in Latin America because it represented a true opportunity to break from the aforementioned traditional power structure. Unlike Facebook, which tries to curate the world’s information to increase our engagement, Twitter is raw, open and immediate, allowing the crowd to determine relevance. All of a sudden voices that were excluded from national conversations can now be heard, and they can determine and influence debates, much like the #BlackLivesMatter (2013) and #MeToo (2017) movements in the United States.

Information that used to be suppressed now achieves its goal of being free. It is no coincidence that the rise of Twitter coincides with the unraveling of a corruption scandal that compares in size and scope only to the corruption inherent in the European colonization of the Americas. In the digital age it is harder to hide information. Corruption, the region’s chief operating system, leaves an Exxon Valdez-sized oil-slick of a paper trail. Those who benefit from corruption are, for the first time, vulnerable.

If information is power, that means that when information is democratized, power is democratized. But the expression of that power, meaning the systems through which that power is exercised, do not necessarily democratize. Indeed, maybe our greatest democratic gap of the modern era is found in the fact that humans can produce a big bang of information every day, but our democracy, as the Argentine democratic hacktivist Santiago Siri has stated, can only process one bit of information per citizen roughly every four years. We have sophisticated users trying to stuff their sophisticated thoughts, expressions and identities into a system with wildly outdated hardware and software that appears to be infected with a powerful firmware virus called corruption.

And not everyone has an interest in upgrading the software. In the same way that a small number of powerful Bitcoin miners can prevent Bitcoin from increasing the block size, there are powerful actors who benefit from preventing an upgrade to democracy. Principally, those actors who have figured out how to hack and monopolize the old system will seek to ensure the new system does not threaten their concentrated hold on power. Even if they started out as rebels in the old system, as Rafael Correa once did, the rebels eventually learn how to be successful in the old model and hence become its strongest defenders.

Indeed, the staunchest defenders of concentrated power are those who hold that power. Increasingly desperate to stay at the helm, the holders-on employ mafia-like tactics to defend their mafia-like organizations, all in the name of their good intentions and sacred causes wrapped in a bow of “for the people.” In this world, however, there is only one truth, and that truth weaves a thread between all Latin American governments, be they dictatorial or democratic, left or right, loved or despaired: that idea is that the ends always justifies the means.

Twitter threatens the concentration of power of the old system, which is why Twitter becomes the battleground between tyranny and democracy. The winners in the old system, as discussed here, are fighting back, and that fight is coming to a democracy near you. By not taking sides, Twitter is ultimately taking a side. By siding with the trolls in the name of free speech, Twitter is standing against everyone else’s free speech. Twitter’s troll centers in Latin America aren’t an unfortunate minor externality or a regional nuance: they’re a business model that threatens to take away any value that the platform might create. The stakes are unimaginably high.